GENDER, DISABILITY & THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY

To crip the lens is to follow in the footsteps of generations of disability artists, activists, and cultural workers who have refused invisibility. It is to bend the camera away from voyeurism and toward resistance; to unlearn normative aesthetics in favour of narratives forged from pain, pleasure, protest, care, and survival. It means troubling what is considered ‘legible’, ‘valuable’, or ‘beautiful’, and asking whose stories get to be told, and how.

Around the world, disability rights are being rolled back, through stalled legislation, shrinking social protections, and a resurgence of institutionalising approaches. From welfare reforms in the UK to weakened civil rights enforcement in the US, and delayed anti-discrimination laws in Asia and Latin America, hard-won gains are under threat. Cripping the Lens responds to this moment of uncertainty by centring those most often erased from dominant visual narratives: disabled people across the gender spectrum.

In today’s cultural landscape, disability remains among the least visible and least understood dimensions of identity. When it does appear, it is frequently flattened into stereotype, tragedy, or token. This exhibition insists otherwise. It asks: What happens when disabled people claim the frame? Cripping the Lens invites us to look again; to reframe, reimagine, and radically re-envision the stories we tell about bodies, identities, and the politics of being seen.

This exhibition is the outcome of the This is Gender: Gender & Disability Global Open Call. Spanning continents, gender identities, lived experiences, and visual strategies, the works in this collection explore how gender and disability entangle, disrupt, and reconstitute one another. Gender shapes how disability is read; disability reshapes how gender is lived. Yet these overlapping realities are routinely excluded from our galleries, archives, media, and policy spaces. Even within our own This is Gender collection, we recognised a profound absence, an erasure that the open call and this exhibition directly confronts.

Here you will find meditations on chronic illness, expressions of queer kinship, documentation of systemic neglect, and declarations of joy. You will find resistance to the sanitised, the inspirational, the pitiful. Each image was selected by a panel of disabled artists and visual culture experts to ground the exhibition in peer-led, disability-informed curatorial practice.

Cripping the Lens is not just an invitation to look differently. It is a demand to reckon with what is at stake when disabled lives, especially those shaped by intersecting systems of gender, race, and class, are erased, misrepresented, or ignored. At a time when commitments to building fairer, more equitable institutions are being rolled back and access is reframed as excess, this exhibition asserts that inclusion is not a luxury, it is a matter of justice. To crip the lens is to confront the systems that render some lives disposable, and to insist on futures in which disabled people are not merely seen, but centred, supported, and celebrated.

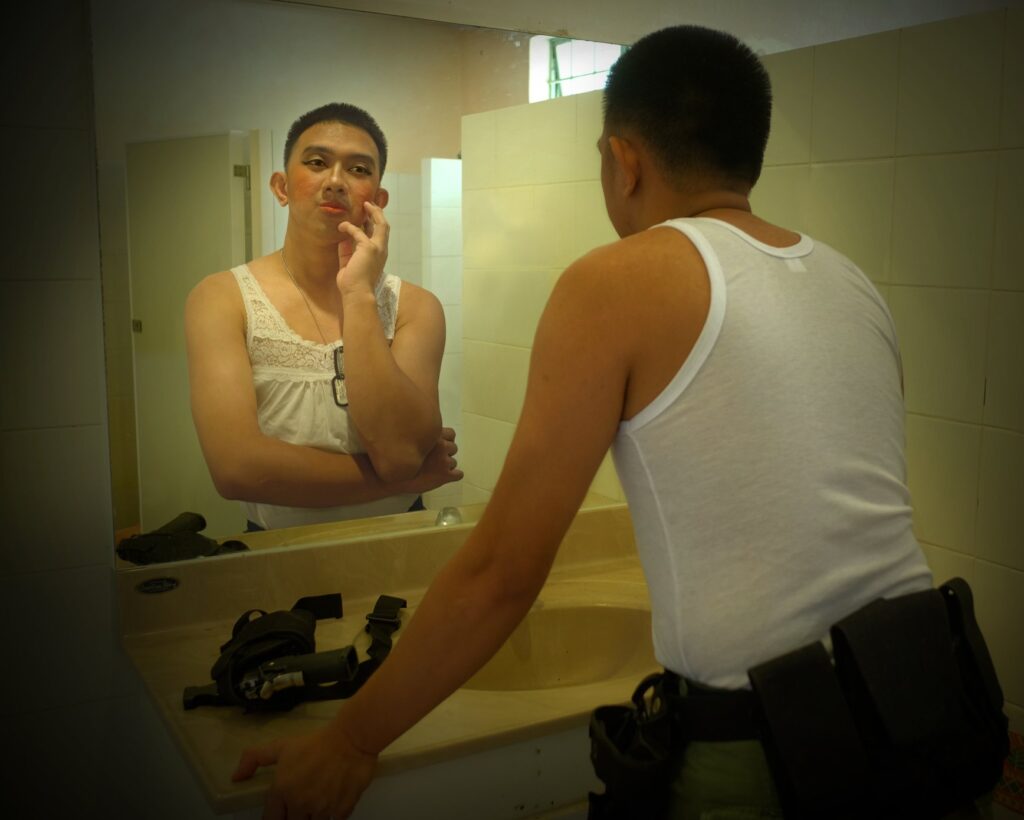

SYSTEMS OF POWER, STRUCTURES OF EXCLUSION

Winning image:

WHEN THE MOUNTAIN WON’T MOVE, HEALTHCARE MUST, (Banawe, Ifugao, Philippines. 2023) Gina C. Meneses.

What the judges say: ‘The dramatic use of light imbues this image with an almost painterly quality, elevating the everyday into the sublime. Visually arresting, the work powerfully reflects key themes of the competition- access, care, health, and respect- rendered through a lens of intimate realism.’

What happens when the very systems that shape our lives—education, healthcare, employment, and law —are built to exclude?

For disabled people, exclusion is often not a failure of the system, but its design. Institutional frameworks routinely sideline disabled individuals, embedding inequality through inaccessible schooling, discriminatory hiring practices, inadequate healthcare provision, and punitive welfare regimes. These exclusions are rarely spectacular. They unfold in policy loopholes, bureaucratic indifference, and infrastructures that privilege certain bodies while denying others.

In this section, artists confront the deep bias embedded in our institutions and imagine otherwise. From the erasure of disabled women in work and education, to the fraught performance of masculinity in militarised and uniformed roles, these works hold up a mirror to systems that marginalise and celebrate radical reimaginings. Lush portraits of peer-led care, disabled-run businesses, and transformative mentorship offer glimpses of what equity might look like.

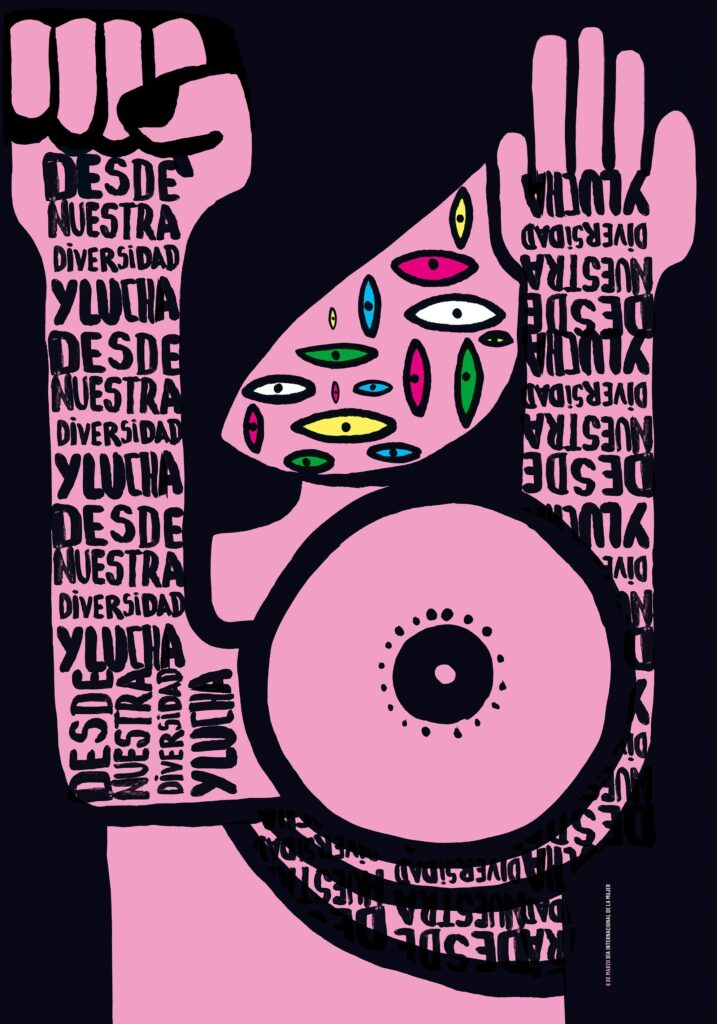

Natalia Volpe

(Mexico City, Mexico. 2025), Jenny Bautista Media

(Tamarin, Mauritius. 2023),

Neco Nahaar Abdul Carim and Hana Telvave

Luciano Santiago Abadis

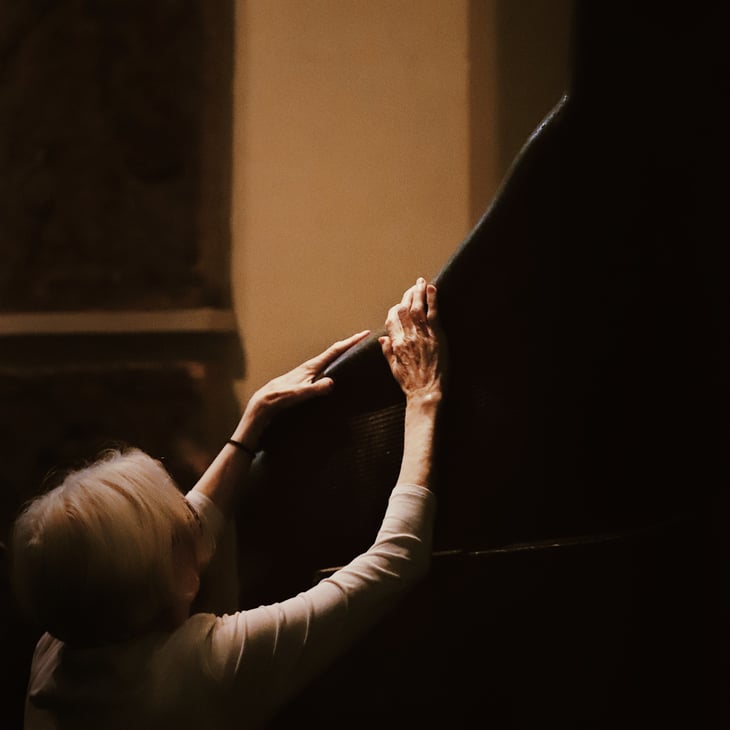

CLAIMING SPACE, SHAPING PLACE

Winning image:

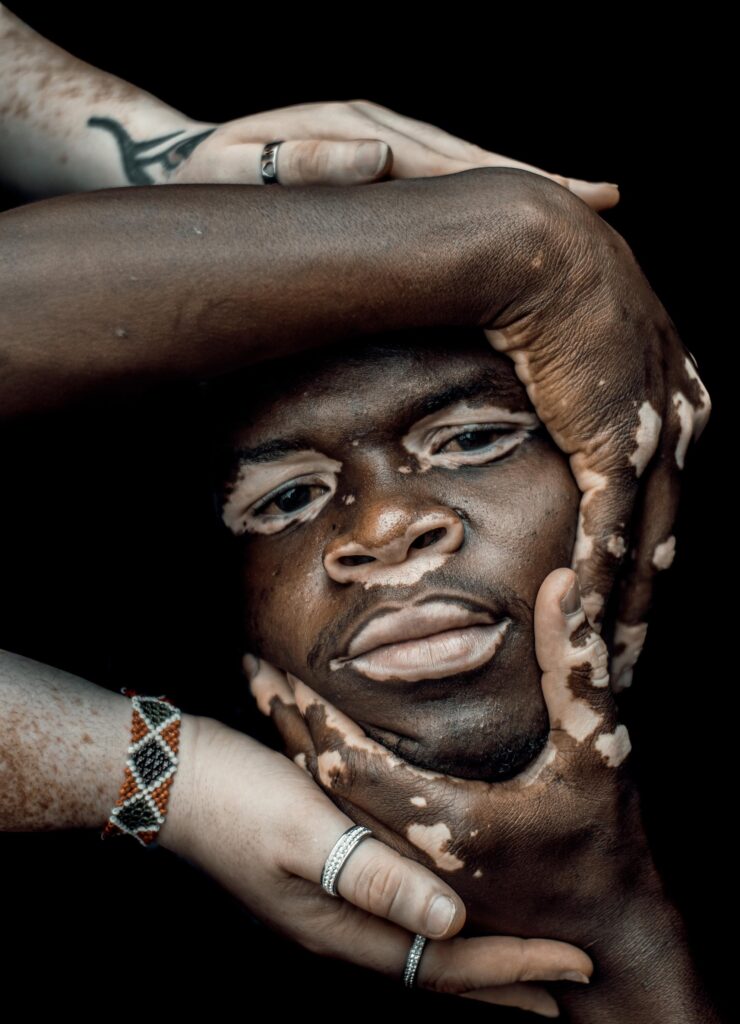

THE PAST IN YOUR HANDS, (London, England. 2024,) Jaime Prada

What the judges say: ‘The hands dominate the frame, contorted yet graceful, resembling tree branches reaching through darkness. The visual emphasis on her hands- her tools for navigation- transforms the image into a powerful meditation on touch, accessibility, and embodied knowledge.’

Space is never passive. It is structured, contested, and deeply political.

Whether designed with intent or neglect, space reflects the values of those in power, and often excludes those whose bodies, movements, or perceptions fall outside normative design. For disabled people, space is not simply something to move through, it is something to navigate, resist, and sometimes remake.

This section traces that negotiation: from the hard edges of urban infrastructure to the quiet intimacy of interior worlds. Here, hands map history, bodies press against borders, and a room becomes a refuge.

Moving across geographies and scales, the artists expose space as both material and metaphor: a terrain of control and a site of possibility. Through their lenses, we’re asked not only who space is built for, but what it could become when designed with care, creativity, and accessibility at its core. We are encouraged to think spatially and politically, to see access not just as a feature of place, but as a condition for justice.

RELATIONS OF CARE, ACTS OF RESISTANCE

Winning image:

ACOMPAÑAMIENTO Y CARIÑO, (Mexico City, Mexico. 2025), Jenny Bautista Media

What the judges say: ‘The unguarded nature of the embrace, captured in rich monochrome, elevates the photograph beyond voyeurism. It is a portrait of trust, resilience, and quiet defiance, an assertion that love, intimacy, and care belong to all bodies.’

Care is one of the most contested terrains of disability politics.

Often framed as something done to disabled people, typically by able-bodied others, and filtered through gendered assumptions of duty, sacrifice, and dependence. This narrow lens reduces disabled life to passivity and obscures the rich, reciprocal networks of care that disabled communities build every day. In this section, care is reclaimed, not as burden or obligation, but as a practice of agency, intimacy, and collective survival.

These works explore how disability and gender together shape the ways we love, parent, desire, and sustain one another. They trace the architectures of chosen family, the quiet strength of interdependence, and the deep ties forged through shared experience. Here, care becomes a radical act, a refusal of the systems that isolate, devalue, and pathologise. Care is not just support, it is strategy, resistance, and world-building on terms defined by disabled people themselves.

Jaime Prada

NOVI, CHORUS OF LIGHT, (Yogyakarta, Indonesia. 2024), Ryan Andrew

Jacenty

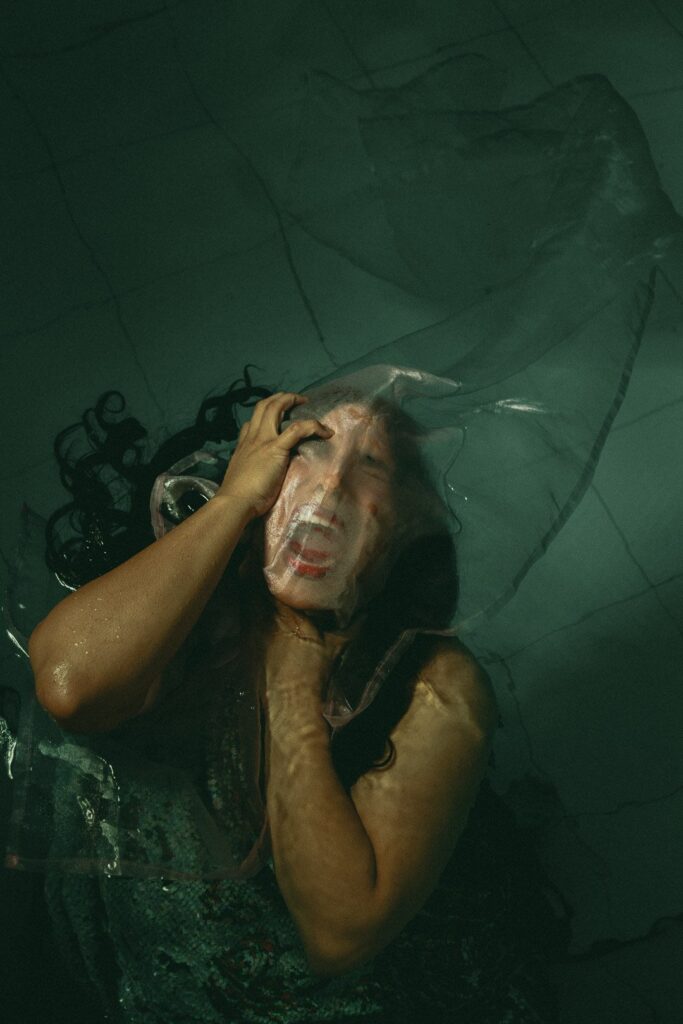

THE BODYMIND AS ARCHIVE

Winning image:

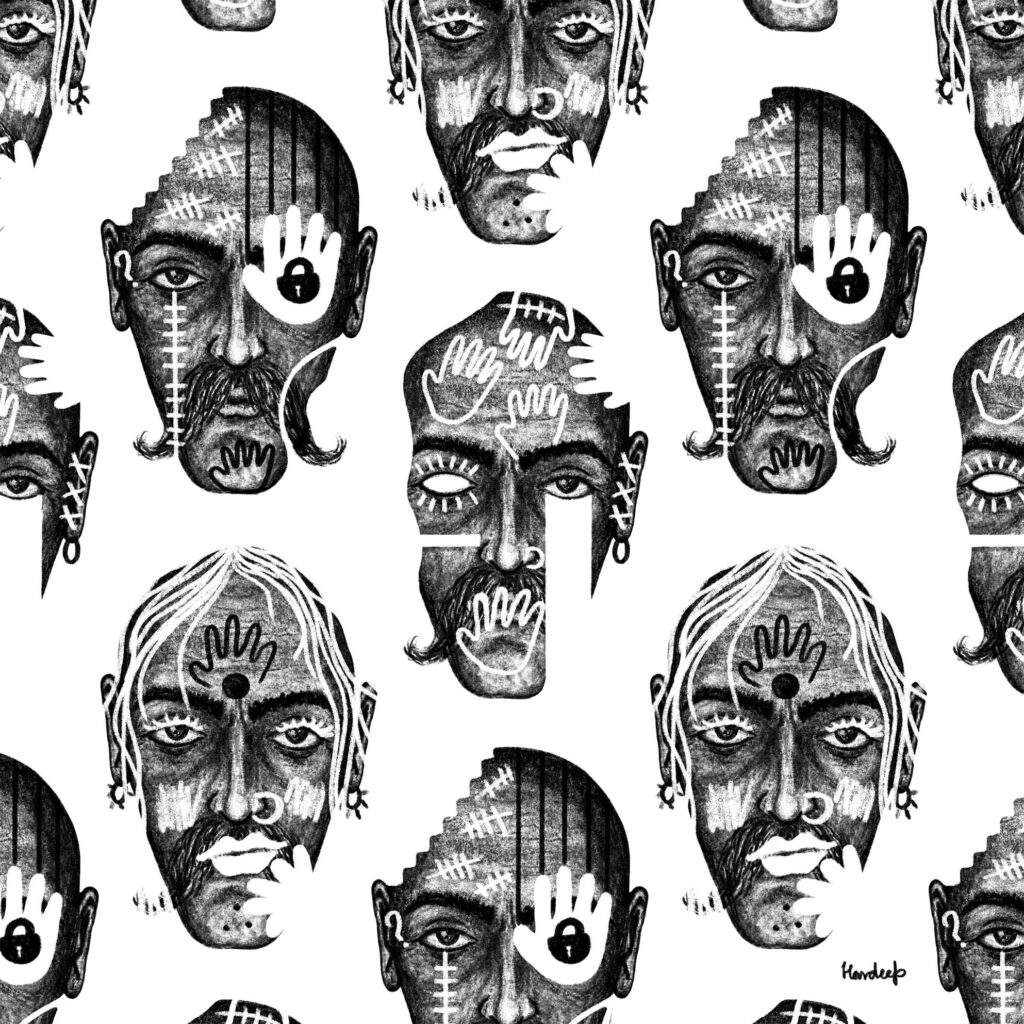

FRAGMENTED FACES, (New Dehli, India. – 2021), Hardeep Singh

What the judges say: ‘This printed work thoughtfully references sign language, using it as both subject and structure to explore alternative, embodied modes of communication. The hands partially obscure the face, drawing attention to gesture as a primary site of expression. The composition’s patterned and abstracted form echoes textile design, reinforcing the work’s engagement with language as something felt, seen, and performed rather than spoken. A compelling meditation on how the body itself becomes a medium of meaning./

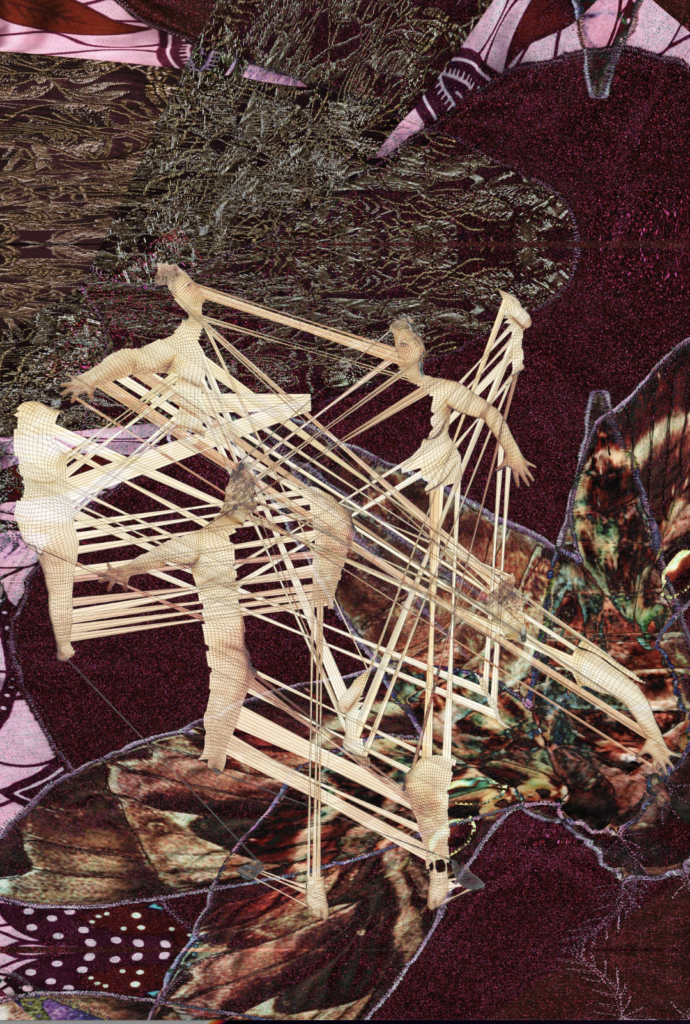

The bodymind is archive, instrument, battleground, and guide.

In this section, artists turn inward, treating the bodymind not as a site of limitation, but as a source of knowledge, resistance, and transformation.

These works explore embodiment in all its complexity: as memory, boundary, expression, and terrain. Some images pulse with pleasure or pride, others with fatigue, estrangement, or grief. Together, they resist fixed narratives, revealing embodiment as shifting, sensate, and deeply political.

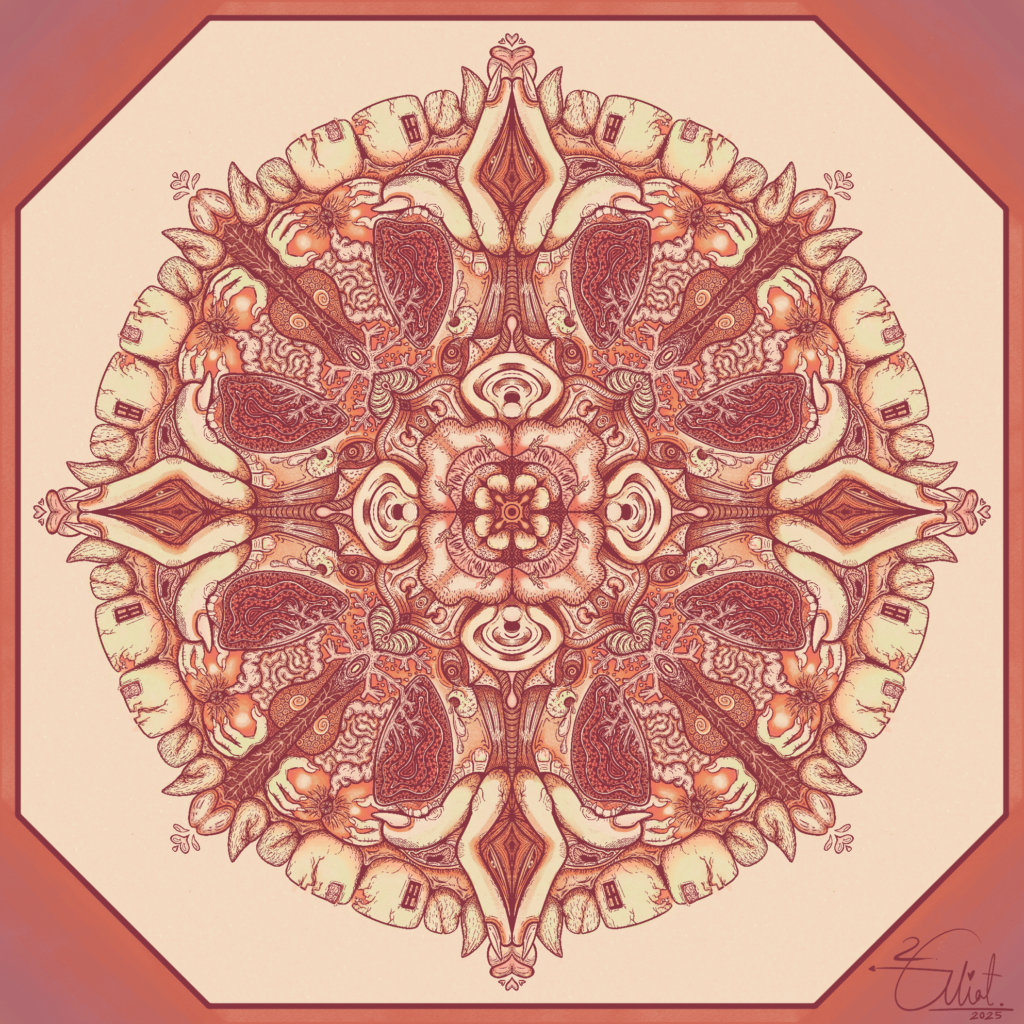

Here, gender is not static, it is felt through pain, performed through gesture, and negotiated through skin, texture, weight, and touch. Across photography, abstraction, and performance, these artists make visible the intimate, ongoing negotiations between flesh, identity, and becoming.

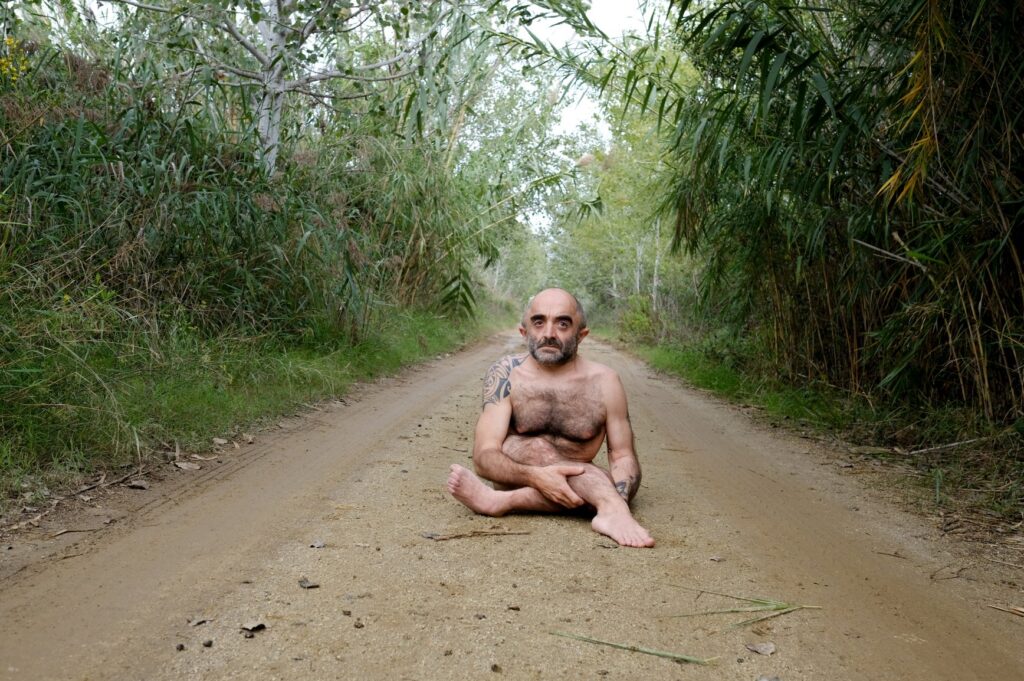

Arianne Clément

Michael Dorohovich

Mark Barrable

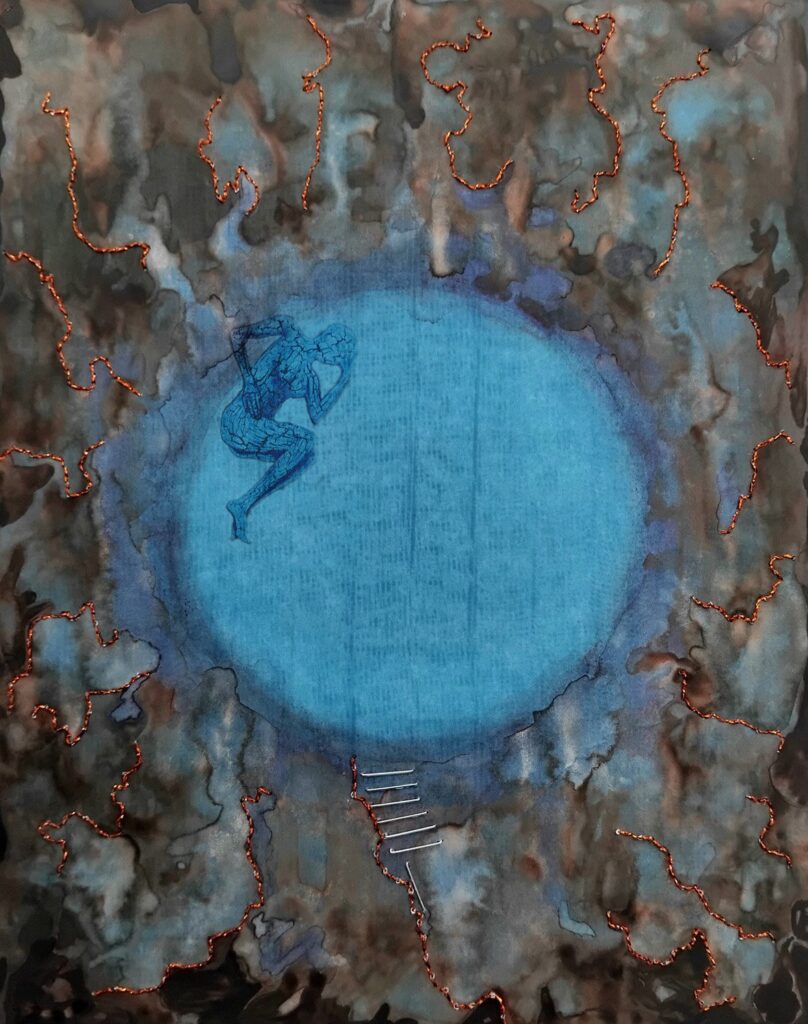

WORLD BUILDING AND RADICAL PRESENTS

Winning image:

HOPE NEVER DIES, (Bangladesh. 2022), Sadman Sakib

What the judges say: ‘A luminous, spontaneous image that captures the radical potential of joy. The entire series is exceptional; powerful storytelling with depth and tenderness, paired with outstanding artistic execution.’

Across this section, worldbuilding is not metaphor, it is method, necessity, and refusal. Whether through sport, gardening, performance, protest, or play, the artists here show how disabled people continually remake the conditions of their lives, not in spite of constraint but in defiance of it. These acts are not escapist, they are grounded, intentional, and often collective. In creating space for pleasure, care, movement, and imagination, these works ask what becomes possible when we build from disabled and gendered ways of knowing and being.

Worldbuilding pulses through the entire exhibition. Across varied geographies, bodies, and forms, these artists expose exclusion and craft alternatives. They challenge what is, while offering blueprints for what could be. Whether through spatial reclamation, acts of care, or the intimate terrain of the bodymind, they show that disabled life is not something to be fixed or framed, but a generative force for reimagining the world. Worldbuilding, here, is both practice and politics: a way of resisting, reshaping, and living otherwise.

(Kurdistan Region of Iraq. 2017), Claire Thomas

The judging panel and collaborating organisations

The Cripping the Lens images were selected from hundreds of submissions by a panel of expert judges, all of whom bring lived experience and deep knowledge from within the disability community. We are deeply grateful to them for their time, insight, and critical engagement in shaping this powerful selection of work.

Longlisting Panel

- Asha – National accessArts Centre Curatorial Programme

- Carla S – National accessArts Centre Curatorial Programme

- Eve Johnson – National accessArts Centre Curatorial Programme

- Kathy M Austin – National accessArts Centre Curatorial Programme

- Mark Bedford – National accessArts Centre Curatorial Programme

- Sherrine Fox – National accessArts Centre Curatorial Programme

Shortlisting Panel

- Carbon – Black trans artist, activist and academic

- Shamim Salim – Founder of Henna Space; an organising space for Queer Muslim Women and Queer Disabled folks

Cripping the Lens was developed in collaboration with CREA and the National accessArts Centre (NaAC). We thank our partners for their shared commitment to amplifying disabled voices through the arts.

Critical Vision: Judges on Image, Power, and Representation

In this series of short videos, members of the Cripping the Lens judging panel reflect on the complexities of visual representation, the politics of visibility, and what it means to select images through a disability justice lens. Their reflections offer a window into the values and questions that shaped the final selection.

How do representation and creative practices contribute to disability justice?

What barriers still exist in how disability and gender are represented in art and media- and how can artists break them down?

What common misconceptions around disability do you want to dispel, particularly when it comes to representation and visual storytelling?

Where next?

See more bold, brilliant images from the competition and dive into our collection of over 250 visual stories.

Dive into the creative processes, visual ethics, and exclusive behind-the-scenes details of selected images in our Representation Matters series.

For inquiries about Cripping the lens, or simply to share your thoughts, contact our curator Imogen Bakelmun at imogen.bakelmun@global5050.org.